[responsivevoice_button rate=”1″ pitch=”1.2″ volume=”0.8″ voice=”US English Female” buttontext=”Story in Audio”]

The Pandemic is Making the Suburbs Even More Appealing

Safety has always warmed the suburban soul. The American dream is sometimes equated with property ownership and the nuclear families such properties house—but really, they are just hulls for a more fundamental suburban aspiration: individualism, which the suburban home demarcates and then protects.

“The American dream was Every man gets his castle,” Todd Gannon, the head of architecture at Ohio State University’s Knowlton School, told me. Above all else, the suburban life is one of independence, a self-contained homestead where the American family can realize its desire and potential, unperturbed by others. Even the family car gets its own bedroom.

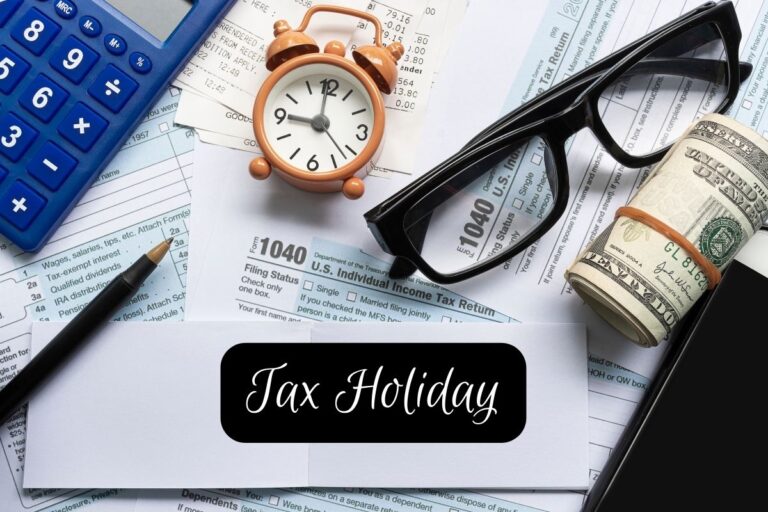

This independence was always mythical, in part. The tax base that suburbia generates often can’t support the infrastructure required to sustain it—roads, sewers, schools, emergency services, and all the rest. Along with federally backed mortgages and mortgage-interest deductions, the suburban lifestyle amounts to an enormous government subsidy, or else it slowly decays into disrepair.

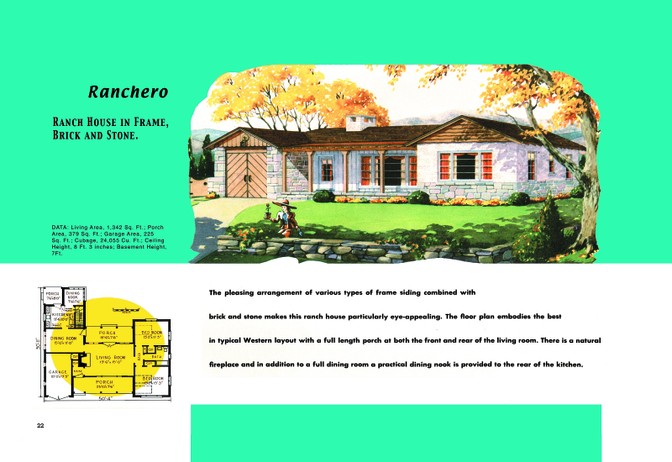

Suburbia makes the illusion of self-sufficiency material. Even the architectural design most strongly associated with it, the American ranch home, borrowed its name and style from a fantasy of autonomy. Broad and rambling, the ranch transforms the real western ranchero into a set of symbols: of wide, open spaces offering opportunity; of a family in charge of the land and therefore its own fate; even of the good breeding of livestock, now transformed into the rearing of children.

When the American dream is framed as independence rather than communalism, the benefits of city life start to seem like detriments instead. In urban environments, for example, walkability connects people to local commerce—something single-use residential zoning eschews in favor of car trips. That’s why the architect Andrés Duany, who also co-founded Congress for the New Urbanism, has likened single-family residential communities to an “unmade omelet,” wherein the eggs, cheese, and vegetables represent homes, work, and commerce that are unnaturally separated from one another. Mixed-use development, by contrast, offers shops, restaurants, and offices within a stone’s throw of apartments and condos.

But rejecting mixed-use planning has made suburban communities unexpectedly resilient in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s not so appealing to be able to walk to the corner café for brunch (a cooked omelet, presumably) when the venue has been shut down by shelter-in-place orders. Even as restaurants and retailers reopen, dining in or shopping has been degraded by the coronavirus: Restaurant occupancy is restricted by social distancing; establishments are struggling to make ends meet; and worries about contamination in enclosed, air-conditioned spaces damage the experience. All of that might return to normal eventually, but by the time it does, the gastropubs and ice-cream parlors may have gone under anyway. The coffee shops may convert for good into tableless pickup stands. Commercial catastrophe will affect the allure of existing mixed-use developments far more than single-use, low-density residential communities, which never relied on those benefits as a condition of residency.