[responsivevoice_button rate=”1″ pitch=”1.2″ volume=”0.8″ voice=”US English Female” buttontext=”Story in Audio”]

Online School Is Harder Thanks to Unequal Internet Access

In Cooper’s school district, for instance, there are some areas that internet providers haven’t hooked up, and others where getting internet would be too expensive for students’ families. “You pay $200, $300, and your internet’s still horrible,” she said.

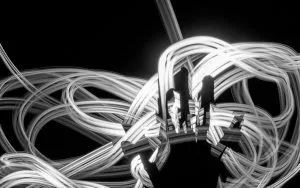

Even in normal times, this digital divide holds back the unconnected in innumerable ways. Broadband access tends to boost local economies, because many companies run on the internet and employers tend to take job applications only online. Many areas that lack internet also lack doctors, but telemedicine can’t reach places where few people have a connection strong enough for FaceTime. People without internet might have trouble accessing news and information, which has steadily migrated online. In areas where broadband exists, but not everyone can afford it, teachers still assign homework online, and only some students can complete it.

Read: These 8 basic steps will let us reopen schools

A lack of internet access can be a source of embarrassment, says Sharon Strover, a communications professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “Many people are acutely aware of their inability to quickly whip out a phone that can connect to the internet without thinking about how much it’s gonna cost.”

In countries such as South Korea and Sweden, governments built out broadband infrastructure and opened it up to internet providers to use, much like the interstate highway system in the U.S., says Roberto Gallardo, the director of the Purdue Center for Regional Development. But the U.S. mostly left this up to the internet companies themselves, and parts of the country got overlooked. Typically, internet companies say there aren’t enough customers in certain areas for them to feel financially incentivized to go there. This occasionally leads to what advocates call “digital redlining,” in which wealthy areas get online, while lower-income neighborhoods don’t. Similar to residential redlining, this has a disparate racial impact: Black Americans are less likely than white Americans to have a broadband connection at home.

“When I worked at the FCC, I fielded phone calls from consumers who would say, Why is broadband deployed two blocks from me, but when I call the provider, they say,‘It’s going to cost us tens of thousands of dollars to bring it to your neighborhood?’” says Chris Lewis, who worked on broadband access in the Obama administration and is now the president of Public Knowledge, an advocacy group for internet access. Meanwhile, in about two dozen states, it’s illegal or very difficult for cities to build out their own internet networks, in large part because of lobbying by internet companies.

Read: What happens when kids don’t have internet at home?

When the government does entice internet providers to go into underserved areas, the companies aren’t held accountable if they fail to connect all of the people they promised to. For instance, CenturyLink received $505 million a year for six years from the FCC to expand rural broadband. The company did not meet its targets, yet it was not sanctioned by the FCC, and it is still eligible for a new round of federal funding this October. (In response to a request for comment, CenturyLink said, “The FCC’s CAF II program rules provide flexibility to address real-world challenges that arise as rural networks are built out. CenturyLink is on track to achieve full deployment in all states well within the time period specified in the FCC’s rules.”)